The Real (Sex) Meaning of Purim

Reading TheWanderingJew’s post the other day about Purim porn got me thinking about where Purim comes from. Most people would say, “well, of course, it comes from Shushan (Susa).” That’s only marginally correct.

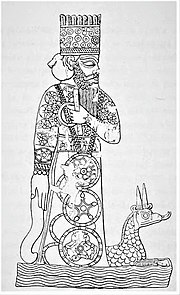

Isn’t it weird that the hero of our story Esther has a name so much like the Assyrian/Babylonian goddess Ishtar?

We have Mordechai. Sumerian/Babylonian and Akkadian civilization had (has?) Marduk.

The Secular Humanists have more:

The original characters appear to have been Babylonian gods: Ishtar, the goddess of fertility; Marduk, the chief guardian of the heavens; and Haman, the underworld devil. Ishtar and Haman, life and death, vie with each other for supremacy. Ishtar triumphs; spring returns; and life is renewed. YHVH, the Hebrew God, played no part in the celebration, which was filled with theatrical renditions of the contest. Noisemaking and masquerading were necessary to trick the evil gods and to aid the good ones. Sexual orgies promoted fertility. Merriment was the order of the day.

I wonder if this fertility rite, which gave birth to Purim, has left it’s initial meaning with us in the form of tri-cornered yannic sweets full of tiny seeds. The hamentashen, of course, originally were filled with poppy seeds. The yiddish word for these seeds, mun, when combined with the name for pocket, taschen, gave rise to the modern word. I first heard this linguistic history from Marga Hirsch. I suspect though, that it isn’t so simple as being an Akkadian fertility cookie since it seems to have popped up in Eastern Europe. Is there a Sephardi or Mizrachi equivalent?

I should also point out that, as tight as the case may seem there is some substantial dispute on whether our near-eastern holiday with similar sounding characters is, in fact, related to older near-eastern rituals, holidays, etc. I haven’t weighed deeply into the linguistic analysis but my initial read is that most of the blowback is by Jews who are shocked, SHOCKED, to hear that many of our hagim are re-framings of pre-existing holidays. Perhaps they believe that someone else having something similar clouds our specialness or makes it seem less clear that ours is holy and theirs is a corruption of God’s word. I don’t worry about those things. (More accurately I worry about them insofar as people worrying about them is worrisome and damaging to world peace.) The case seems a pretty good fit, so let’s sit back, read megillat Ishtar and enjoy our deeply western-semitic story. Perhaps if you want to get very close to the original Purim, you might want to edge more in the direction of bacchanalia.

My family is from Eastern Europe and that poppyseed filling is in positively everything; I wouldn’t read too much into its presence in hamentaschen.

Blah blah. Marduka was a very common Babylonian name. Ishtar, or various forms of it, were popular with women also. Theophoric names aren’t the sole property of the Hebrew people. Just ask Adele Berlin’s commentary on the book of Esther (JPS, 2001).

These aren’t really theoric names so much as hebraicized names of deities. Are you really suggesting that it’s a coincidence that we have a feast the same time of the year with Moderchai and Esther as the older neighbor holiday focused on Marduk and Ishtar?

For all we know the date of this idolatrous holiday was chosen by Haman as when to wage war and exterminate the Jews of Persia. That would make sense – kill the Jews in the name of some idolatrous god and party! There is a basic problem with anthropology – any given set of data can be interpreted fifty different way, and each one could still be wrong.

We Jews have an extensive oral tradition (which has been put in writing for some 2000 years). I don’t see a reason to grasp at straws to test the truthfulness of that tradition. In contrast to other traditions, where it starts from one guy having a dream or getting hit by lighting, or whatever, we are unique in having hundreds of thousands, if not millions of Jews bear witness to open miracles. Can any two Jews agree on anything on this blog?! 🙂 So imagine millions of Jews making a pact to lie to their children… it would never happen. I think any such revisionist history needs to pass a basic intellectual threshold – why would hundreds of thousands if not millions of Persian Jews agree to lie to their children about what happened on Purim?

Everyone thinks I’m attacking them. I’m not attacking you, ZT. Maybe I sound reactionary… I should work on the way I write. You have an interesting theory, but you’re also asking us to question 2500 years of accepted Jewish history based on someone’s imagination in interpreting ancient events to which they were never a party.

So imagine millions of Jews making a pact to lie to their children… it would never happen. I think any such revisionist history needs to pass a basic intellectual threshold – why would hundreds of thousands if not millions of Persian Jews agree to lie to their children about what happened on Purim?

The Kuzari argument strikes again! Nice Purim Torah.

Victor,

If you believe that Megillat Esther is meant to be understood as factual history I think you have a bigger problem than the way that you write.

We have a whole segment of haredim who do not gradually craft and tighten a narrative over the course of generations, but blatantly lie to their children that the world is literally 6,000 years old, and macro-evolution a falsehood.

Kol v’ chomer…

Great post! It’s quite interesting that, according to what I have read, the Persian new year of that time involved casting lots to see who the new chief court official would be. So the Book of Esther is a reflection of, or a parody of, that tradition: Haman seems to win, but it’s Mordechai who comes out on top. Esther’s story also has links to the descent of Ishtar: for example, Ishtar spends three days in the underworld just as Esther does fasting, Ishtar also has a rival queen (Ereshkigal, queen of the underworld), and Ishtar also has a wedding with the king (to confirm the king’s sovereignty). Again, the book could be a reflection of the ancient Near Eastern epic, or a parody of it, or both. How funny it would have been to Jews to imagine that Jews had infiltrated the pantheon of their host country!

On another note, Victor, you seem to be assuming that Jews would consider the Book of Esther (or of Exodus) a lie if it wasn’t factually true. I’m a bit confused by that. Ancient peoples understood what myth was, and they knew what poetry was. Stories can reflect people’s views of themselves without being factual.

Megillas Esther is so obviously in the style of farce that it’s painful. Like Yeilah pointed out, it’s like opposite day.

There’s a yiddish song from the shtetlakh that I think is called “Oy itz gut tzit zein a yid” (I’m sure i just butchered the yiddish) Oh it’s good to be a Jew. It’s about a dude from the shtetl who encounters numerous people that it could be unsafe for a Jew to encounter: a priest, a kossack, a tax collector or something like that. And he hits them in various ways, and laughs and sings “oy itz gut tzit zein a yid.” The megillah is the same way, this could not have happened in exile and it’s funny to have it happen in the way that it does. Imagine it put on stage and performed nearly exactly as written, it’s funny.

And I just want to point out that it wasn’t Persian Jews that decided the megillah was to be included in Tana’kh. And to compare what happens in Megillat Esther to the revelation of Torah (which is where Victor’s argument actually comes from), well, that just seems problematic.

Victor, mainly out of curiosity, do you see a difference between (capital T)Truth, truth and fact? And is “myth” equitable to false in your mind?

So imagine millions of Jews making a pact to lie to their children… it would never happen.

as opposed to Christians making a pact to lie to their children about their mythos? Or Animists lying to theirs? C’mon.

It is intellectually enlightening to read about these parallels and potential origins of this particular megillah and holiday. But it does not follow that because there exists this parallel, then the whole holiday is pagan or based in avodah zara.

Every Jewish holiday can be found to have some pagan precursor. So what prompted people to recast that precursor into something that was Jew-ish? How did we interpreted the story and the rituals initially and up through the present?

If Purim is indeed a farce, then I can only imagine it was a farce created to satirize the idolatrous worship of the time.

Perhaps, in preparation, we should all get in touch with our inner-Tom-Lehrer.

I can’t help but imagine that the Babylonians would be a bit disappointed by our modern day rendition —

“You mean there’s no orgy?”

“No, but if you wave this thing in the air it makes noise! Here, have a cookie.”

They could form a support group with the ancient Greeks we invited to our seder last year.

zt, care to provide any historical evidence that such a holiday existed on the Babylonian side of things?

Samuel, very good point. I didn’t mean to imply that purim wasn’t Jew-ish, so much as that it seems to have it’s primary basis in a pagan pre-cursor. I think it’s a good step towards humility to acknowledge that we borrowed here-and-there over the years and the result was a religion somewhat like and unlike others in it’s historical time and place. Certainly there has been much staying power to our minhag and mythos and that’s a good thing, mostly.

tzachi,

Are you suggesting that perhaps Marduk was lifted from Mordechai? As you could have read in the link Marduk was already commonly known in Hammurabi’s Babylon (18th Century BCE). The Megilat Esther is about 1500 years younger.

zt-

but neither of those things are substantial historical evidence, they are merely conjecture–compelling conjecture to be sure, but just conjecture. And I do not think that Tzachi is suggesting what you’re saying. Think of it this way, the flood narrative in the Gilgamesh pre-dates the Torah by a good millennium, but the fact that both texts share a similar narrative does not mean that the Torah “lifted” those similarities from Gilgamesh, but rather that people in the region who were of different ethnic background had similar myths reflecting on similar shared experiences.

Historical evidence and “things sound the same” are pretty different things…

No need to add on to what Justin said…and far be it from me to say “those goyim got it from us!”. Hey, come to my seder where I go on and on about what afikoman actually is.

Justin,

What sort of evidence would you need to consider it probably that Purim is a hebraicized version of a pre-existing Babylonian holiday? Theirs is about 1500 years older, the main characters have basically the same names and the plot is directly related (albeit ours is more complex)? Would we need to have video footage of a conversation where Jewish leaders decided that they needed a version of this for our guys?

oops, probable not probably

zt-

a) I’m not saying that the conjecture is incorrect, just that it is not historical evidence. I couldn’t tell you what historical evidence would look like, but that similar names and being older is not evidence, again, that doesn’t mean it’s not the origin, just that it’s not grounded historical evidence.