A Jewish Survivor of the Sabra and Shatila Massacre on a Lifetime of Activism

Ellen Siegel at the Sabra and Shatila Massacre commemoration ceremony on September 20, 2014.

When longtime activist Ellen Siegel recently wrote us saying she had suffered from a debilitating stroke and was in need of financial support for her rehabilitation, I was prompted to review her interview with the American Jewish Peace Archive. I found a story of courage and dedication. In her September 2014 interview, Siegel shared the story of her lifelong work with Palestinian refugees in Lebanon — including during the 1982 Lebanon War — her peace activism within the U.S. Jewish community, as well as her advice for younger activists who aspire to follow in her footsteps.

Siegel’s memories of Israel start early. She remembers the jubilation in her Jewish neighborhood in Baltimore in 1948 on the day Israel was declared a state, including “a parade up the street where people were carrying the Israeli flag and singing ‘Hatikvah,'” Israel’s national anthem.

In the late 1960s, Siegel got involved with the anti-Vietnam War, Women’s, and Civil Rights movements, while working professionally as a nurse. Her political involvement led her to progressive circles within the Jewish community, where she began to learn about the history of Palestinians for the first time.

In 1972, Siegel took a trip to Europe and the Middle East with another young Jewish American woman. Seeking to better understand the conflict and the history of the region, they traveled to Lebanon and visited a Palestinian refugee camp. When they arrived, one of the PLO guards there told them, “We killed Israelis at Munich.” Siegel was taken aback and confused. She didn’t yet know about the murder of eleven Israeli Olympic team members and one German guard during the Olympic Games by the Palestinian militant group Black September on that very same day: September 6, 1972. Siegel and her friend soon found themselves in a conflict zone when Israel retaliated with an air raid on PLO bases in Lebanon and Syria, which killed both militants and civilians.

Siegel felt compelled to offer her nursing skills to those who had been injured in the raids. As a volunteer with the Lebanese Red Cross, she “saw incredible devastation…There were cars that had been run over by tanks. There were fires.”

In one hospital, Siegel met an elderly man with pictures on his wall of orange groves, which he said were from his home in Palestine. Throughout her time in the hospital, Siegel continued to hear similar stories from Palestinian refugees of longing for home in what was now Israel.

After several months in Lebanon, Siegel and her friend traveled to Israel and spent two months living on a kibbutz. At one point, they took a taxi to El Arish in the occupied Sinai Peninsula.The cab driver told them, “Why do you want to go there [and] see these dirty Arabs?” Siegel recalls being deeply disturbed by the racism she encountered.

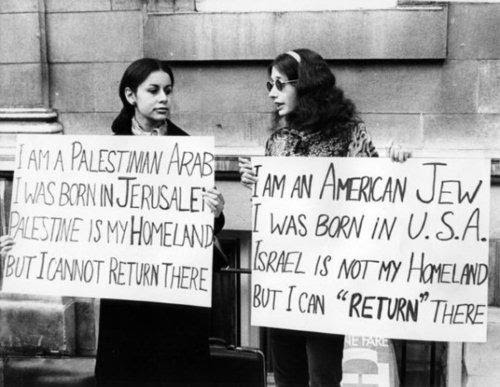

|

| Ellen Siegel with Ghada Karmi in 1973 |

She remained connected to the Palestinian refugee community in Lebanon after she left, and, in 1980, Siegel returned to Lebanon where she had been helping to promote the work of a women’s embroidery collective. She saw very little improvement in the overcrowded refugee camps in the eight years since she had last been there. In fact, parts of them seemed worse.

Back in the U.S., Siegel helped found Washington Area Jews for Israeli-Palestinian Peace in Washington, D.C. in the summer of 1982. Theorganization started as an ad hoc group of Jews who organized protests in front of the Israeli embassy against the bombings and siege of Beirut during the Lebanon War.

At the end of that summer, Siegel felt that, given the horror of the war, she needed to do more. So, in August 1982, she returned to Lebanon as avolunteer nurse and was assigned to Gaza Hospital, serving the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps.

In September 1982, Lebanese president-elect Bachir Gemayel was assassinated by a member of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, and Israeli forces occupied West Beirut. The Israeli Defense Force (IDF) surrounded theSabra and Shatila refugee camps, and allowed their then-allies and enemies of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) — the Christian Phalange militia — into the camp to “clear out” any remaining PLO militants. The Phalange were out for revenge as they believed Gemayel, with whom they were allied, had been murdered by a member of the PLO. The IDF shot flares to light up thecamp to enable them to see into alleyways.The Phalange massacred hundreds, perhaps thousands of Palestinian refugees — including many women, children and elderly people — in the Sabra and Shatila camps, while, according to Siegel, the IDF blockaded anyone trying to flee. The Israeli military also provided walkie-talkies to communicate with the Phalanges, as well as bulldozers to bury the bodies.

Siegel was working in the hospital in Sabra during the massacre. Initially, many people in the camps ran to the hospital seeking safety and shelter, injured with bullet wounds.

As the violence spread and panic broke out, most of the patients inside thehospital fled, leaving behind only “the critically ill who couldn’t move.” Thehospital staff hid them in the basement. Siegel recalls taping up the windows so explosions wouldn’t shatter the glass.

The next morning, the volunteer international staff were told to go to theground floor of the hospital. Militants, who Siegel recognized as Phalange from the Arabic on their uniforms, were waiting for them. When an Arab staff member of the hospital attempted to join the group of mostly Northern European, white volunteers, the soldiers shot and killed him.

Siegel did not yet know why the Phalange militants appeared to have taken control of the camp, but, with the rest of the foreign volunteers, she obeyed their orders to follow them into the street. She remembers passing by many dead bodies. One Palestinian woman tried to give her baby to the medical staff as they walked by, but was prevented from doing so by the militants.

After taking their passports, the Phalange fighters lined up the nurses and doctors against a bullet-riddled wall. She recalls, that when they “stood in front of us with their rifles, many began to cry. I thought to myself, ‘Is anybody going to know that I died in this refugee camp?’ But, I thought, ‘it’s okay that I did this, because this is the right thing to do.'”

But an Israeli commander ran into the group and ordered the Phalange soldiers to halt the execution, presumably because “it would not have looked nice if all of these foreigners were assassinated.” Siegel and the other volunteer medical staff were then taken to a U.N. building where they were individually interrogated about why they had “come to help Palestinians.” Finally, their passports were returned and they were turned over to the IDF.

Siegel recalls how incongruous it was to arrive at the IDF post, on top of a hill overlooking the camps. It was Rosh HaShanah, and some of the soldiers were wearing prayer shawls and kipahs while reciting morning prayers. One memory in particular stands out to Siegel decades later: one of the Israeli soldiers offering a piece of honey cake wrapped in tin foil to one of the Norwegian volunteer nurses. She thought: “this man’s mother gave him this honey cake for a sweet year to take with him on his journey and here he was standing in aplace where hundreds if not thousands of people had just been slaughtered.”

When she told him that she wanted to testify, Siegel was connected to theIsraeli authorities. Soon after, she was brought to Jerusalem with two other doctors who had worked with her to testify before the Israeli Commission of Inquiry into the Events at the Refugee Camps, otherwise known as the Kahan Commission.

|

| Ellen Siegel with colleague Dr. Swee Ang in Jerusalem prior to testifying before the Kahan Commission, Oct. 1982 |

When she was called to testify, Siegel read her written statement aloud. She ended by saying “that Jews have spent many years looking for war criminals and bringing them to justice” and that she hoped that “justice would be done.” She was told by Justice Aharon Barak, chairman of the Commission, that justice would be done. “Of course,” Siegel reflected, “justice was never done.”

Siegel believed that then-Defense Minister Ariel Sharon, as the person overseeing the IDF’s operations in Lebanon, was guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Siegel recalls that IDF soldiers were “on top of thefive-story building [with] binoculars, looking down on the camps. And they could see. They knew what was happening.”

The Commission found Sharon personally responsible “for ignoring the danger of bloodshed and revenge” and “not taking appropriate measures to prevent bloodshed.” He was later dismissed as Defense Minister by Prime Minister Menachem Begin, but only after a massive outpouring of grassroots pressure by Israeli activists.

“Ever since then,” Siegel said, “I’m known as the nurse who testified against Sharon. But I have done a lot more.”

When Siegel arrived back in D.C. in November 1982, she continued her involvement with Washington Area Jews for an Israeli-Palestinian Peace. One of her roles within the group was organizing Friendship Dinners in the D.C. area to promote relations between the local Jewish and Palestinian populations. The dinners grew to accommodate about 200 attendees, including prominent Jewish and Palestinian community leaders. Siegel also maintains good relationships with Israeli peace activists, many of whom she has helped arrange speaking tours in the U.S.

|

| Siegel speaking with Rabbi Sid Schwartz at Friendship Dinner in the mid-1980s. |

Since her testimony over 35 years ago, Siegel has regularly gone back to therefugee camps in Lebanon to attend the annual Sabra and Shatila massacre commemoration ceremony, as well as to visit schools and clinics to “show solidarity and try to give them the hope that they will one day have the ability to return.” She also works with the Lebanese NGO Beit Atfal Assumoud (BAS), which helps children have a normal kindergarten experience, provides financial support to the elderly, and helps Palestinian women sell embroidery.

As far as her message to younger American Jewish activists who might follow in her path, Siegel first and foremost wants us to understand the severity of thesituation of Palestinian refugees. “There are now at least four generations [born] in these refugee camps… and the children [still] draw maps of Palestine.” Decades after they were created, the refugee camps are still overcrowded, with open sewage systems and without clean water or electricity. She said that young activists “need to understand the history,” and she shared her wish that more people “could go to Lebanon, and have a tour of these camps and listen and talk to Palestinian [refugees].”

I was moved by the story of Ellen Siegel’s activism, service, and dedication over the course of decades. Her interview spotlights a history of horrific brutality against Palestinian refugees in Lebanon and suffering that continues to this day, and reminds us that the struggle for reconciliation is far from over even 35 years after the Sabra and Shatila massacre and Kahan Commission at which she first testified. How the Israeli government can take more responsibility for Palestinian refugees and make reparations for these crimes remains an animating question for Siegel. My hope is that we can learn from her story and carry forward her legacy of courage, commitment and speaking truth to power.

|

| Ellen Siegel at AJPA interview on Sept. 7, 2014 with her cat Dartanian, who was rescued from Lebanon. |

Very informative article about a very courageous person. Well done