American Jews and Race: A Review of “The Color of Love: A Story of a Mixed-Race Jewish Girl”

These are embarrassing questions: why do Jews of color all seem to have stories of having their Jewishness doubted, or of being harassed in a synagogue? If nearly fifteen percent of American Jews are people of color, why are many synagogue congregations overwhelmingly white? Why do some American Jews with minimal religious commitments choose Jewish day-schools over a public, racially mixed option—might that have something to do with race? For many white Jews, Judaism functions as an excuse to live in segregated communities without admitting that they are doing so, an alibi for their racial privilege.

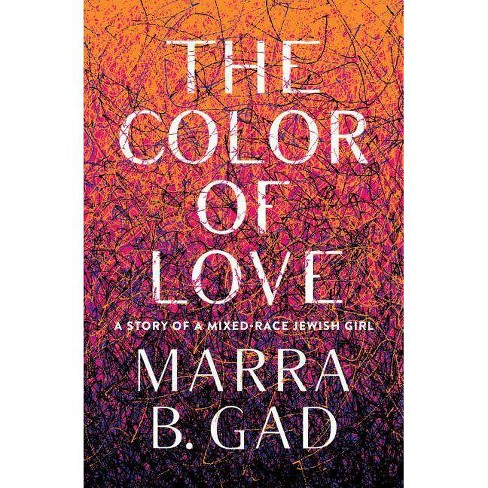

For that reason, it is unsurprising when Jews of color disengage from white Jewish communities, and profoundly moving when they choose to remain connected. Those twin movements frame Marra B. Gad’s new memoir, The Color of Love: A Story of A Mixed-Race Jewish Girl. Adopted by white Jewish parents in a Chicago Reform community, Marra faces constant harassment: from the usher who runs after her to ask what she is doing in synagogue on Yom Kippur, from the white friend from Jewish summer camp and youth group who tells her she is “too complicated to bring home” and the lawyer who flies from San Francisco for a first date because (as he says) “Jewish boys have jungle fever,” even, after her father’s death, from an older saleswoman who objects to Marra’s torn black ribbon because “it is a sign of mourning for Jewish people.” This is a very partial list. One of Gad’s smart observations is how, as she and her family distance themselves from one after another harasser, both micro- and macro-, their social world constricts, and they regretfully withdraw from Jewish community

But worst of all is the ongoing hostility from her Great Aunt Nette. Nette is a colorful figure of excess and transgression: she has married serially and remains in contact with former husbands, dies her hair lavender and wears a floor-length white gown to someone else’s wedding, waltzes and foxtrots and luxury cruises her way through life. As a child, Marra wants Nette to be a couture fairy godmother, an ideal of feminine beauty and glamour whose approval would ease the bodily insecurities of mixed-race, zaftig teenager among white peers. Best of all, Nette’s most recent husband, Zeit, is Chinese, which inspires in Marra a hope of multiracial solidarity. Quite the opposite: Nette is intensely prejudiced, showering Marra’s sister with jewelry and a trip to her and Zeit’s San Francisco mansion while pointedly ignoring Marra. In the memoir’s opening scene, at Marra’s sister’s wedding, Nette snaps and declares her racism forthrightly. The book’s first half gradually unpacks the various traumas behind that moment—Nette’s own history of abuse, the various micro- and macro-aggressions of Marra’s youth, and so on—concluding with Nette’s excision from the Gad family.

Surprisingly, the story does not end there. In the memoir’s second half, Marra comes to care for and, in some measure, to reconcile with Nette. She does so prompted by her great aunt’s desperate situation. When Nette develops Alzheimer’s and Zeit becomes ill, they cannot take care of themselves. Without children and unable to handle their finances or even clean their house, Nette and Zeit are assigned to a state-appointed conservator who controls their finances, manages their day-to-day lives, and has legal control. When the state calls the Gad family, only Marra (who is living in Los Angeles), is able to help, so she begins regularly flying to San Francisco to care for Nette and try to bring her to Chicago. In the process, she alternately has to battle and flatter their conservator, a geriatric tyrant who grossly neglects them, stingily refusing to make necessary expenditures while paying himself a steep hourly salary. As you would imagine, Marra also suffers all the usual harassment and incredulity about her being the black relation of an old Jewish woman. Moreover, Nette herself oscillates between ornery, racist hostility toward Marra (recoiling at her touch, for instance, even as Marra is trying to dress her), uncomprehending confusion induced by dementia, and occasional, sweetness and warmth.

Marra’s choice to care for her aunt is heroic and superogeratory. No one would have faulted her for disengaging. There’s a rabbinic teaching that describes attending to the needs of the dead as “the loving-kindness of truth,” since the dead can do nothing in return; a mixed-race woman caring for a racist, elderly relative with dementia fits roughly the same bill. And though she sticks to her personal story, I cannot resist reading Gad’s memoir as an allegory of contemporary American Judaism: an aging community of largely white, wealthy insiders who have, for decades, pushed everyone who doesn’t fit to the margins, and young Jews, particularly Jews of color, who somehow, miraculously refuse to be excluded.

That latter point seems to me surprising, moving, and potentially redemptive. I don’t know if Gad consciously patterned her title on James McBride’s The Color of Water, the great mixed-race Jewish memoir of the preceding generation. Regardless, the comparison with McBride’s book is instructive. While both tell painful stories of white Jewish racism, the earlier memoir plots away from Judaism toward McBride’s Jewish mother Ruth finding a more loving, accepting form of Christianity. By contrast, Gad’s story offers a Jewish mode of love, on the integrity of a Jewish mixed-race family, and the possibility of repair. (To be sure, this contrast reflects difference of circumstances and social class. As excruciating as Gad’s story is psychologically, it takes place against the comfortable, well-to-do background of private schools, parents who own the building in which they live, and so on.)

Yet Gad’s hopeful conclusion also reflects a generational difference. Recent years have seen the emergence of Ammud, a “Jews of Color Torah Academy” in New York, the return of Yitz Jordan (Y-Love) to performing and the promise of a new collaboration between him and Rabbi Shais Rishon (Manishtana), and Ilana Kaufman’s groundbreaking demographic study of Jews of color. And there is much more. It is a newly live possibility that the American Jewish world might become genuinely multiracial, as American Jews already are. In short, those presently in control of our community and institutions have much to learn from reading The Color of Love and similar books.