The Vort – Mishpatim – Freedom From, or Freedom To?

The Ishbitzer rebbe, the brilliant and controversial chassidic thinker of the late 19th century (copies of his book Mei HaShiloach were burned for their radical ideas), writes about the huge distance between this week’s parasha, Misphatim, and last week’s parasha, Yitro. In Yitro, God shatters the barriers of heaven and earth, descending in all God’s glory on a mountain and speaking directly to an entire nation. The Jewish people reach extraordinary levels of consciousness, seeing sound and hearing color. Smoke and fire rage. It is the highest, most intense spiritual moment the Jewish people have ever experienced. Then, we have Mishpatim, which begins with:

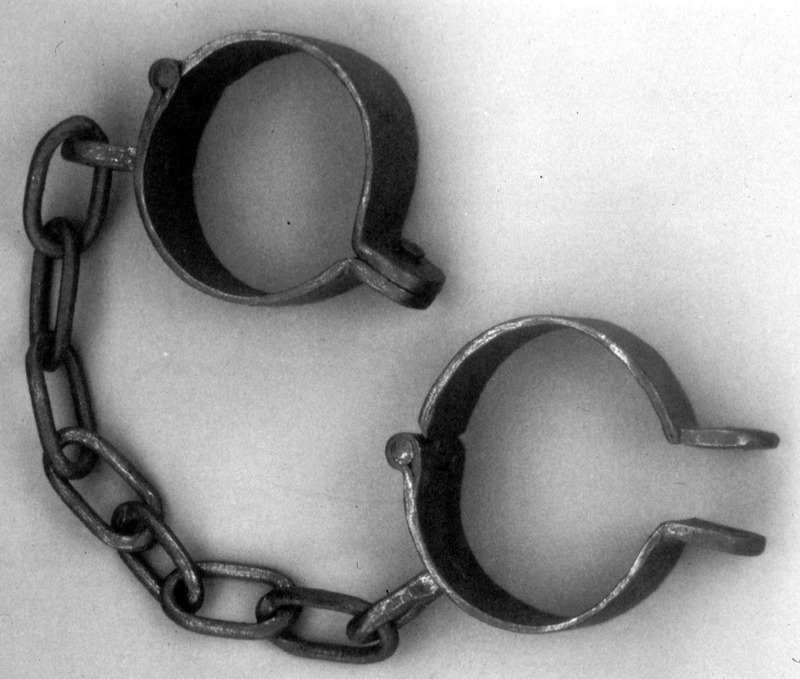

Now these are the laws which you shall set before them: If you buy (תִקְנֶה) a Hebrew servant, six years he shall serve; and in the seventh he shall go to freedom, for nothing.

Now Torah, really? The first thing we get after revelation is how to deal with our brothers and sisters who are slaves? That’s so unseemly, so low. We’re a nation who just saw God! We just escaped from the most powerful country in the world! We’ve accepted our responsibilities as a chosen people! This is what you want us to think about?

The Ishbitzer writes that yes, this is exactly what the Jews are supposed to think about coming off their collective high from last week’s parasha. Yitro, he writes, represents the world of abstract thought – lofty ideas and values. Mishpatim, according to the Ishbitzer, signifies the “entry of Jewish people into the world tikkun (repair).” And tikkun happens in the dirty details, the tachles that actually changes the world. “Want proof?” the Ishbitzer continues, “look at the wording – the verse says: if you ‘תקנה’ a Hebrew servant.” The word for buy, תקנה has is just one letter away from תקן – to repair.” The radical transformation of the world that Judaism requires of us doesn’t happen through thinking ideas in our heads, no matter how big or grand those ideas may be. Tikkun happens when we look at our most basic individual and communal practices and tweak them them, one at a time. This is the Jewish people’s freedom. It’s not freedom from slavery. It’s the freedom to change it, and to end it. It’s the freedom to make a world more more just, the freedom to build a world more in the spirit of God.

In the Torah, the Egyptians refer to Israelites as Hebrews but the Israelites never refer to each other as Hebrews (Moses and Aaron refer to the “God of the Hebrews” but that is only so that Pharaoh will understand). The Torah uses the term Hebrew in Mishpatim to indicate that an Israelite who buys a slave is thinking like an Egyptian not an Israelite. The word Hebrew will not occur again until Deuteronomy 15:12 where it is used the same way.

The Torah only uses the term Hebrew one other way, to describe Abram when he goes to war.

Ok, I appreciate what you’re trying to say, and I think it’s even valid. But the reality is that lots of the Torah is still vomit-inducing. And any justification, including that only the ‘bad’ or ‘Egyptian – thinking’ Hebrews, were enslaved, is nothing more than what all enslavers try to do, which is to justify our actions because deep down I think we all know what we’re doing and we’re trying to live with the horror by dulling our spiritual eyes.

Someone- I kind of agree, but I think the fact that the torah can feel vomit inducing is because “dibra torah bilshon adam” – the Torah speaks in the language of Adam. A lot of humanity is vomit inducing. Torah’s for humanity, so it’s gotta work with what it’s got.